Recovery Plan

Goal setting

What things do I want to be able to do again?

Sometimes it can seem very difficult to see a way forward. This may be especially true following an injury and a period of reduced activity. We tend to lessen our activity following injury. Things that you took for granted become much more difficult and you may find yourself avoiding certain activities all together. Very often it’s the enjoyable things that fall by the wayside. People generally find that setting some goals is a useful method by which we can move gradually forward.

How can setting goals help my function?

An important point to remember with all goal setting is that progress towards the final target or objective will probably need to be broken down into steps or stages, each with smaller goals along the way. Goals are not just there to test us. They are a way of moving from where we are to where we want to be. They help us to recognise our own successful progress and allow us to reward ourselves when each new goal is achieved. Research has also shown that being active will speed up your recovery.

The five steps in goal setting: SMART

Specific: state exactly what you want to achieve and how you’re going to manage it. Make sure it isn’t vague. e.g. ‘I want to get fit’ is too vague, fit to do what? How will you know when you’ve achieved it? ‘I want to be able to swim 3 lengths’ is more specific.

Measurable: ensure your goal is measurable: How will you know when you have achieved your goal? “I want to feel better” isn’t a very good goal because it’s not specific and it’s difficult to measure. “I want to be able to walk 1.5 miles, on the flat, by x date” is a better goal because it’s specific and measurable.

Achievable: ask yourself whether the goal is within reasonable reach. For instance, completing a marathon may not be an achievable goal in the near future if you’ve never run before. However, completing a 1km run may be.

Rewarding / enjoyable: this is really important. We are unlikely to do something if we don’t see the point or don’t enjoy it. So make sure it is something you want to achieve because you used to enjoy it.

Time limited: try and decide upon a time frame. Being able to track your progress encourages you to keep going and reach your goal. Look for ways to chart your improvements.

Tips

- Check that your goal will fit in with your life or make changes so that it is a priority.

- Make sure you want to and will do the goal.

- Don’t set it because you feel you should, or someone else said you should.

- Write your goal down, get some support and encouragement, and reward yourself when you succeed!

Examples of a goal that follows the SMART Formula:

Goal: to drive a 1 hour journey

When do I want to achieve it by: 4 weeks

How I’m going to do it: draw up and stick to a driving plan.

John wanted to achieve this goal. Initially he could only sit for 30 minutes in the car. He set himself a plan to build up his activity over a period of 3 weeks, using a stepped approach. He stuck to this plan on both good and bad days. At the end of three weeks, he had built his activity levels up sufficiently to be able to achieve this.

Think about what realistic and achievable goals you would like to achieve and then complete section 1 of your recovery plan.

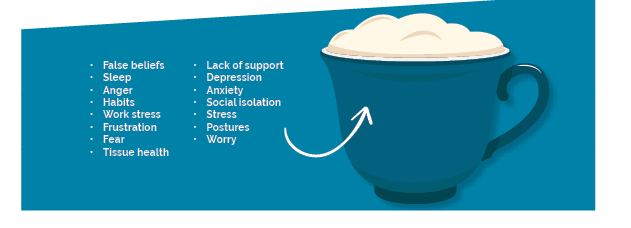

Things that may aggravate pain - “the overflowing cup”

What things are causing my cup to overflow and what can I do to reduce their impact?

As pain persists it becomes less about tissue damage and more about anything in your life or something particular about you that can make you more sensitive. Remember, pain is normal but what happens when it persists is that we get better at it. In a sense, we have an over-reactive and over-protective system.

Its easier for the pain to be “triggered’ and multiple things in our lives can contribute to this. Its not just about muscles, tendons and joints (although they are sometimes important). Its everything in our lives. For example, big tough football players are more likely to get injured when they have a lot of physical/mechanical stress. That is what most people would expect. But athletes are also more likely to get injured when they have a lot of academic stress. Dancers are more likely to get injured when they have poor sleep or higher levels of anger/hostility.

Look at pain as the overflowing of a cup. Many things contribute to what is in that cup. You can have a lot of physical, mechanical, emotional and social stressors and have no pain. But at some point a sudden increase in one of those stressors or a new stressor puts you just over the edge and the water flows out and now you have pain. Often people will have more pain when there is a change in the stressors in their life. It is the inability to adapt to the new stressor that contributes to pain not necessarily the amount of the stressor in your life.

Pain occurs when we fail to tolerate and adapt to all the stressors in our life. Its not stress - its unmanageable stress. We need to keep that cup from overflowing.

The multidimensional nature of pain means there are a multitude of things that can help with pain. You can decrease one contributor a great deal or perhaps address a few of them. What you can also do is BUILD A BIGGER CUP. This means over time you can build resiliency or coping that allows you to adapt and tolerate all the stressors in your life. Most people can’t run a marathon today. But people can slowly build their tolerance to the stresses of running and do it soon. Pain recovery and coping is the same thing. You can decrease some of the stressors in your life but also build resiliency to those stressors.

What’s in your cup?

The main barriers to recovery

Beliefs

Many false beliefs about pain can continue to sensitise your nervous system. If you believe that movement and load is bad for the body and will cause injury then you will be likely to withdraw and avoid activities even though those activities are good for you. Your beliefs might lead to bad decisions for your pain.

Lifestyle/Health social factors

What areas of your life can you be healthier? Consider:

- sleep

- stress

- work-life balance

- obesity

- general health conditions

Sensitivity can be influenced by a number of factors. Consider what you can change.

Coping strategies

Do you avoid or do you persist? Avoiders stop doing the things that are important to them or certain movements and this avoidance leads to increased sensitivity. Persisters keep doing the things that aggravate them and they never get a chance to settle down. Find the balance!

Emotional/Psychological factors

Fear, catastrophising, depression, anxiety and anger can all contribute to your sensitivity. Are you getting help in these areas? Do you think you need help?

Think about the things that cause your cup to overflow and complete section 2 of your recovery plan.

How to improve my ability to do things

Building a bigger cup

Fortunately, some of the things that decrease all of the contributors to pain can also increase the size of your cup or build your tolerance to life’s stressors. Things like:

- general exercise or physical activity

- resuming hobbies or meaningful activities

- working with a counsellor on stress management

- getting a started on a consistent sleep schedule

- giving your body permission to move and explore any movement, movements should be fearless - we are designed to move!

- changes to your diet

- almost anything that makes you happier

- focusing on your successes!

Think about what you would be doing if your pain was less of a problem for you. Pain does not mean you have to stop doing most things in your life. Remember, persistent pain means that you have an overactive alarm and it is much less about damage and more about the need for protection. The problem is we overdo that protection. We have to convince you, your body and your brain that you don’t need that protective response anymore.

There is nothing about you that needs fixing before you start doing! The doing is the fixing.

The Role of Exercise in building a bigger cup.

Physical activity helps with pain for a number of reasons. Just getting your heart rate up a little bit can give some people mild pain relief. In others, a little bit of strength training can help pain improve in the long term. Physical activity is one of those things that BUILD A BIGGER CUP. It is a general desensitiser and improves your tolerance to all stressors. When you combine physical activity with learning about pain, changing your habits, resuming meaningful activities and changing your beliefs they can all add up to helping you get your life back and get out of pain.

Physical activity can even decrease the sensitising chemicals that are involved in some osteoarthritis. Remember, stressing yourself is how we adapt. Physical activity can provide that stressor.

When you first start doing exercise it can be difficult to know if you are exercising at the right level for you and your pain. Section 4 is there to help you with this.

Tips

- Choose something you enjoy.

- Choose an activity that you actually want to do.

- Keep an activity diary or reflection diary to track your progress

- Use a graded approach to exercise (to help with this see the next section).

Graded Exposure

How do I know if I’m doing too much or too little?

Graded activity enables you to gradually increase your ability to do a particular activity or position in a stepwise manner. e.g. sitting or walking.

Principles of graded activity

1. Work out your starting point — That is how much of the activity you can do now, without overdoing it. This is the amount you can do on a good day and on a bad day. E.g. if you can manage to walk for 10 minutes but it’s a real struggle, maybe your starting point is 8 minutes. Baselines can be in any unit of measurement (time, distance, number of lengths, number of shirts ironed, no of lampposts walked past etc)

2. Write up a realistic plan for the week ahead

3. Make sure the plan progresses in small equal steps. Progress every day, every second day or every third day- keep increases small but consistent.

4. Stick to the plan on good or bad days. It is tempting on your good days to do a lot more, then do less on the bad days. Make sure therefore on the good days that you pace yourself and don’t overdo it. On the bad days stretch yourself a little.

5. Review the plan at the end of the week and make and necessary changes. If you have had one bad day- progress the plan at the same rate. If you have struggled a few days in a row this would suggest you have been too ambitious and need to slow the rate of progression down in next week’s plan. If you feel you could progress quicker, speed the rate of progression up.

6. Expect some increased symptoms as you increase your activity, this is normal, to be expected and will settle. Your plan should be realistic and will therefore keep any increased symptoms to a minimum. Remind yourself that you are not harming yourself, your body is already sore and is bound to complain as you ask it to do more.

7. If your activity levels are significantly increasing your symptoms or your symptoms are lasting longer than 24 hours then then reduce your activity or slow down your rate of progression.

Work with your physiotherapist to complete sections 3 and 4 of your recovery plan.

Flare-up management

What are flare-ups?

When we have a persistent pain problem it is common to experience setbacks. A setback is usually characterized by a sustained increase in symptoms

- They often have triggers – these can be physical or negative thoughts or feelings. They may not be immediately obvious.

- There may be situations that make the setbacks more likely

- There is often a vicious cycle that maintains this setback

If you can identify your triggers you can reduce the likelihood of a setback. You therefore may be able to break this vicious cycle and manage these situations better. As a result you may find that setbacks become less problematic, you can manage them better, they don’t last as long and you can get back on track much sooner.

How do I respond to a flare-up?

When symptoms become really bad it is difficult to do anything else but dwell on them – this is natural but can get in the way of recovering quickly from a setback. How we respond to that increase in pain and what we think about it will often influence how quickly we recover from a setback. If we think the worst when we experience a setback and reduce our activity levels it can often take a long time to recover. However, if we view setbacks as a normal part of a pain problem, and are reassured that it is safe to get moving, we often recover much quicker.

Remember that setbacks are usually time limited, so whilst you may need to reduce your activity for a short while, it is important to gradually increase activity in a short period of time.

Flare-up emergency plan

- Don’t panic – this will get better

- Accept it has happened

- Assess whether this is a new pain or a familiar one

- Check your thoughts

- Try to relax ie: 7/11 breathing

- When you feel ready do some gentle exercises

- Modify your activity

- Reassure yourself

- Reframe how you view your flare-up

- Take some of your usual medication if necessary

- Return to normal activities as soon as possible

- Congratulate yourself for managing it well

- Reflect on and learn from the experience

Managing triggers

Initially there may be a trigger which causes a setback. We may have an excessively busy day which we weren’t expecting, or we may forget to take our medication, or we may receive some bad news about something. As a result of this our pain can often increase.

We may be able to control some of these triggers. For example a common trigger for back pain is sustained sitting. By taking regular breaks from sitting, by getting up and stretching, we can reduce the chance of a setback from happening. Other techniques to reduce the chances of setbacks from happening include doing exercises, going for a walk, changing to another activity, or doing relaxation exercises.

However, in spite of employing these techniques there will be times when setbacks cannot be avoided. Setbacks are not always triggered by particular activities and not all triggered pain is controllable. However, through applying the techniques recommended in the setback emergency plan, the impact of setbacks can be reduced.

Think about what you can do in a flare up and complete section 5 of your recovery plan.